Effective Use of Real-Life Experiences of Cancer Patients as a Training Strategy in a Nursing Degree Program

- Corresponding Author:

- Anna Maria Grugnetti

Experimental and Forensic Medicine Department

University of Pavia and San Matteo Hospital of Pavia –Italy

Tel: 39 0382987290; 39339 5338980

E-mail: annamaria.grugnetti@unipv.it

Abstract

Effective Use of Real-Life Experiences of Cancer Patients as a Training Strategy in a Nursing Degree Program

Keywords

Patient cancer, Nursing education, Teaching-learning strategies, Hope, Support

Introduction

In healthcare and in nursing education, the value of cancer patients’ views is recognized as extremely important. In our University, during the three years nursing degree program; the holistic care of cancer patients is recognized within the curriculum, and the training includes a deep understanding of each patient’s beliefs. This comprehensive process is not easy for students [1-3]. For this reason teachers promote an enhancement in students understanding of patient’s story, developing their ability to comprehend the patient’s wholeness (body, mind and spirit) and to understand the power of active listening, in order to establish a good relationship with the patient, with the aim of a continuous health care quality improvement.

Patient narratives are a fundamental process to contribute to improve future health professionals’ education. Narratives are a powerful tool that can contextualize and humanize the knowledge required by health practitioners and can facilitate a deeper understanding of the self and others through self-reflection, as well as encourage transformative learning among student. Qualitative research is a methodology that is strongly focused on the understanding of human experience as it is lived, through the collection and the scrupulous analysis of qualitative, descriptive and subjective materials.

To explore biographies a range of methods have been used, which include experiences, narratives, oral histories, case histories, case studies, autobiography, life story and personal histories [4], and storytelling [5] have been used to encourage reflectivity and empathic understanding in relation to individuals and particular. The use of patients’ narratives in teaching and learning helps to generate meaning in the classroom and place the patient at the center of the care process [6,7]. Narrative has been used in healthcare education to enhance self-awareness, critical analysis, cognitive learning and clinical reasoning skills.

Ironside illustrated how using narrative as a teaching learning strategy assists students to compare their assumptions and to evaluate and understand situations from a variety of perspectives. By recognizing the value of patient-centered approaches to healthcare and encouraging teaching strategies that promote this, educators can highlight the difference between biomedical understandings of pathophysiological processes of a medical condition and the individual patient’s subjective experience of living with that condition.

The authentic patient voice needs to be central in the training of future health professionals; short stories emphasize the human dimensions of medical and nursing care. The phenomenology approach is one of discovery and description, and emphasizes meaning and understanding in the study of the lived experience of individuals [8] and translates personal lived experience into consensually validated social knowledge [9]. Phenomenological research seeks to understand the changing experiences and outlooks of cancer patients in their daily lives, what they see as important, and how to provide interpretations they give of their past, present and future [9,10].

The identification of real life experiences told in a story can facilitate learning, professional development, understanding, meaning finding and self-exploration and can make a case for using story as an aid to learning. Telling stories, sharing stories and writing stories are all powerful teaching approaches; to promote professional identity and healthy behaviors [11]. Jones suggests, in relation to the use of literature in medical education, that it may ‘‘help physicians develop empathy, especially for those who are different from them in gender, race, class, or culture’’ and recognizes the need to include patients’ stories of illness. The use of teaching literature must serve the student to reflect on the real situations experienced by the patient in order to provide effective responses to the needs of such patients in the clinical context.

The narrative approach is brought into the clinical practice as a tool that enables perception and interpretation of the illness process, and as a way for healthcare professionals to incorporate new wording to the interpretative repertoire, thus extending the dialogic, hermeneutic and comprehensive dimension of knowledge and the clinical practice [12]. In this way, narrative can be a reflexive and transforming educational practice and it is considered as an active learning method for healthcare professionals. Active teaching and learning methodologies are applied to allow students to build knowledge on real experiences and situations, enabling the development of a critical reflexive vision of the presented content as well as the autonomy and responsibility due to obtain these knowledges and facilitates problem solving approaches to complex but real situations from clinical practice.

Patient’s or career’s voice within the palliative care setting has emerged as a powerful tool that helps others to understand connections between patient’s experience and professional practice in a meaningful way. This is supported by other authors [9,13]. Patients feel that their experiential knowledge of illness can benefit future health professionals as well as other patients, therefore it should be included in medical education.

In literature, there are several qualitative and quantitative studies that address the issue of pain, especially in oncology, highlighting the relevance for nursing care. Although pain has become recognized in the last years as an avoidable public health problem, chronic pain continues to exhaust many patients, their families, and healthcare professionals, who are demoralized and discouraged. Unrelieved pain has a devastating effect, not only on patients but also on their family. It can lead patients to desire death, and family and caregivers to feel that death would indeed be welcome [9].

Schumacher coined the term “pain management autobiographies” to reflect the way in which patients wove experiences, beliefs, and concerns together into personal narratives. Painful experience in infants should be anticipated and prevented as much as possible [14]. Cheng [13] in his phenomenological study conducted with pediatric patients’ and their parents’ to explore their perspectives and experiences, showed that pain was still found to be a horrifically difficult problem for patients with oral mucositis.

Narrative highlights how stories can connect to practice and give access to the real world of nursing. The role of the educator can be more concerned with facilitating the exploration of practice rather than just disseminating knowledge [15]. One of the recurring topics during the classroom discussions was the importance of getting to know the patient’s story and how it impacts the nurse–patient relationship. Key themes related to storytelling that emerged during the meetings were listening, partnership, reciprocity, and solidarity.

Learning to understand the complicated ways in which religion functions as a system of explanation and coping on an individual level is crucial for understanding how women are actually experiencing their illness. Research has shown that teaching strategies that involve active learning, such as group work and case studies, encourage the development of critical thinking and dialogue, and allow students to comment on, question and scrutinize the contributions of their peers to motivate each other’s learning [16].

The aim of this study was to describe a teaching strategy based on the experiences data collection and biographical literature review about cancer patients, within a nursing degree program, in order to help students to understand more about the physiological, psychological and spiritual needs of these patients.

Methods

▪ The learning context

In our nursing degree program, during the lectures of Nursing and Research, we adopted a training strategy based on the illustration of cancer patients’ life story, to describe their emotions, feelings, fears, concerns, as well as their hopes through their path-disease. The aim was to help students in developing a reflective analysis to build relational skills for patient’s support. Autobiographical stories had been introduced and used in the drafting of various theses throughout the course, particularly in the third module, which is centered on aspects related to loss and change in cancer patients. The Teaching session in Nursing Research lasted 30 hours. It took place over a period of two months during the first semester of the academic year. It was attended by 210 second-year nursing students who were all enrolled in the same undergraduate nursing program.

▪ Nursing research course overview

The focus of topic was “Pain and suffering in nursing care: research developments and implications for clinical practice and care”. The patient understanding could be the starting point for global assistance, which considers mainly the relational aspect, as an element capable of giving meaning to this experience and to be activated to the extreme of life, to give resources of health and hope for patients and their families. Nurses must consider the pain and the suffering because they are one of the most central issues in the care. However, despite the existence of knowledge and resources to improve the quality of people life, the resistance to the opioid use and underestimation of pain, emerges as a major barriers to pain management; unfortunately suffering is often trivialized and overlooked.

The aim of this teaching strategy based on the patients’ narrative was to get students to gather information from multiple sources and to put it into a cohesive story in order to provide comprehensive, holistic, and individualized care. The overarching aim of this session was also to encourage participants to use biographies and stories to enhance their understanding of cancer patients’ care issues. Specifically, the aims of this session were to expose students to the reality of personal illness and its impact upon the individual and family, to encourage critical evaluation of the papers and texts in a structured way and to help students to contemplate the potential usefulness of these texts from various perspectives.

Methodology

▪ This teaching session focuses and encourages the experiential methodology

Use of real clinical experiences, some of them taken from the literature, and presented to the students in the classroom, highlighting particular phrases, words and expressions used by the patients.

Convey the meaning of hope for patients and their family, through a phenomenological approach

Students had the opportunity to express their emotions, thoughts, feelings, fears caused by patients’

stories reading; furthermore, through the narratives, they were helped to recognize the needs of patients and their families

During the teaching session, students were asked to reflect on the kind of language used by cancer patients and to identify the changes that the illness elicited in their lives.

They also analyzed the best suited decisions to be made for caring considering the needs emerged.

Teachers proposed to students the reading of several qualitative research papers. Table 1 [9,13] shows the range of Papers selected and offered to students.

| Patient’s words within the literature | Paper |

|---|---|

| Vinnie chose to tolerate and keep silent about a period of severe pain in order to improve his chances of receiving experimental chemotherapy. “I accepted the pain because I wanted to receive it [experimental chemotherapy]from Friday to Saturday to Monday I waited [in pain] because I figured that if they treated me for pain I wouldn’t be eligible for the drug.” The chemotherapy was his hope for a longer life: No matter what if I could control the pain I would walk… I know if I could control the pain I would be, like they say, home free… when I take care of that pain and I don’t have the pain then my mood increase, I would say 90% better. |

Coyle [9] |

| I’ve had some horrific pain, and I just about get to a point where oh, I should take something and then I think no, I don’t want to start with anything. It goes back and forth. So I’m really not taking anything.

Margareth - Also I watched my mother all my life. She’s had chronic pain from very real injuries and from very real medical conditions, but she has made it a point to martyr it out. And I don’t say that out of disrespect for my mother. I love her dearly. But her attitude and watching her in pain all my life has made me—it’s my understanding of myself that watching this has made me totally reluctant to endure any physical pain at all. Because I just can’t stand to watch it. I can’t stand to watch it in her and I cannot deal with it myself. |

|

| It was so ulcerated that I couldn’t talk, eat or swallow anything. Even swallowing saliva gave me great pain (informant 3 - child). It was painful, very painful, because my gum was swollen with canker sores on it. When I chewed, it was like I had bitten onmy own tongue (informant 5 - child). Sometimes the pain was so intense that it made my daughter tremble. When she trembled, she tugged me. I felt that when she tugged me, she was venting because the pain was really bad (informant 7-parent). | Cheng et al.[13] |

| I think I do it ... at least I think I can take time for this evil ... and see if in the meantime things change ... just a few years ago the sick like me dying within six months already ... I now, I can pull to two years ... but ... maybe you will think that dying at 45year or die at 47 year….. but little change in two years maybe things change ... and then at least even if I do not I can heal can take time. I always hoped that it hits my hands ...( effects of chemotherapy) hands no ... because I knew it could happen ... but this time it hit me ... last year my hands had become just a little 'violets.. . but this year ... and last week ... I cried, why my hands…..? I hoped to spare my hands……. I was hoping to avoid this suffering…… |

|

| . . . well spirituality to me is really just my relationship with Jesus Christ, that’s my spirituality and that is what you know . . . gives me my peace . . . inside and freedom; it’s my relationship with Christ. That’s what spirituality means to me. I would say your life’s probably mapped out for you and each day is a new day and each day you find different things come along and how you handle them and I believe at times there is help out there to be got and there is somebody who helps you to be strong. |

Table 1: Examples of “life stories of cancer patients” used in teaching/learning session.

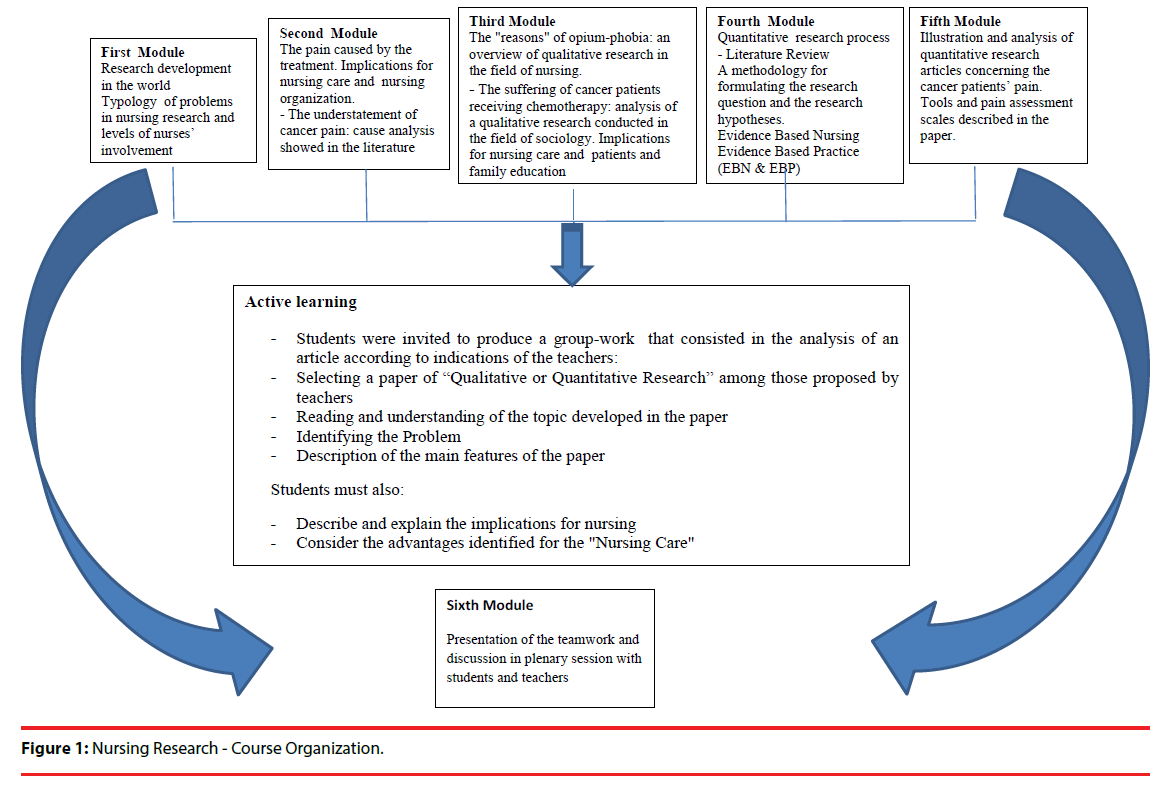

The narrative of real stories has been introduced throughout the course to help students to read and reflect upon the personal impact of serious illness and to understand the importance of the comprehensive relationship. The aim was to encourage the exploration of the of narrative implications for professional caring and to help the students to appreciate the value of the autobiographies in relation to qualitative research. The course is structured in six training modules; the details of this teaching session are presented in Figure 1. Students were leaned by the teachers throughout the teaching/learning process.

▪ Evaluation

Formative assessment is continuous and finalized; it includes the introduction of a team-work to which are assigned a maximum of 3 points, adding the outcome of a written test (multiple choice questions and analysis of parts of the qualitative and quantitative research paper).

On conclusion of the teaching session, a fourpoint evaluation sheet was distributed to have a feedback from the students. The questions asked for participants were: 1) How useful was this teaching methodology for you? 2) How difficult do you think this training session was? 3) How much do you feel this learning experience helpful in your clinical practice? 4) Has this formative experience increased your understanding of patient and his family’s experience? (Table 2) [10,13,17].

| Design | Description | Paper |

|---|---|---|

| Phenomenology | This report analyzes the narratives of seven individuals living with advanced cancer, who describe how both pain and the use of opioid drugs impacted their quality of life, and uses their words to illustrate how the mainstay of cancer pain treatment-opioid drugs were viewed as both a blessing and a burden by these individuals. | Coyle et al. [10] |

| Qualitative phenomenological study | The Author describes children’s and their parents’ lived experiences of oral mucositis (OM) and to explores their needs in relation to OM. Findings from this study illustrate the complexbiopsychosocial impact of chemotherapy-induced OM on children and their parents. | Cheng et al. [13] |

| Autobiographies | The Authors show the experience of several cancer patients about their reluctance to take drugs for the severe pain control. A key finding was that some patients’ reluctance to use analgesics stemmed not only from concerns about opioids but also from a conviction that medications in general are toxins that should be avoided whenever possible. | |

| Phenomenology | The two Authors report their reflections about th e stories of cancer patients who tell what they feel, how they live the disease. These authors describe in detail the feelings of suffering, anguish, fear, loneliness that these people experience, but also their desire for normality, that is, to do the same things they did before falling ill. | |

| Hermeneutic phenomenology | The paper reflects on a study which explored the role of spirituality in the lives of women during the first year after being diagnosed with breast cancer. The study used a qualitative method (hermeneutic phenomenology) designed to provide rich and thick understanding of women’s experiences of breast cancer and to explore possible ways in which spirituality may, or may not, be beneficial in enabling coping and enhancing quality of life. | |

| Hermeneutic phenomenology | This study explores the lived experiences of patients in day surgery who were having an excisional biopsy under general anaesthesia with a view to gaining a deeper understanding of their individual experiences and the meanings that it holds for them. | Demir et al. [8] |

| Quantitative study (Randomized Controlled Trial) | This study was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of oral cryotherapy in preventing oral mucositis and reducing its severity in chemotherapy patients, as well as in helping the patients to feed themselves, preparing them both physically and psychologically. | |

| Quantitative study cross-sectional study | In this paper, the authors described the use of the McGill Pain Questionnaire for the evaluation of chronic pain (more than three months) following mastectomy or lumpectomy combined with complementary treatment (radiotherapy or chemotherapy), in 30 young women with Breast Cancer. | Ferreira et al. [17] |

Results

Students presented twenty-two group-works. Fourteen groups of students chose qualitative studies and eight students group chose quantitative studies. All selected articles described the topic of pain in children or in adult patients. During the teaching session students showed interest in these aspects; students’ comments were positive, as students felt that the session encouraged more critical analysis and included patients’ spiritual dimension recognition.

The findings from the evaluation sheets are presented in Table 3. Students felt that the session was enjoyable and they perceived the benefits of this learning opportunity.

| Questions | Little N. % |

Enough N. % |

Much N. % | Very much N. % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) How much this teaching methodology was useful for you? | 17 (8.71) | 145 (74.35) | 33 (16.92) |

|

| 2) How much did you think difficult this training session? | 20 (10.25) |

110 (56.43) | 53 (27.10) | 12 (6.15) |

| 3) How much you feel this learning experience can be helpful to you in clinical practice? | 23 (11.79) |

151 (77.443) | 21 (10.76) |

|

| 4) As this formative experience increased your understanding of the experience of the patient and his family? | 34 (17.43) | 107 (54.87) | 54 (27.68) |

Discussions

This teaching/learning strategy have been used to encourage reflectivity and empathic understanding in relation to cancer patients and particular contexts, deepening mainly with the aspects related to pain, as described by Powell Our experience about this teaching session is that biographical stories can offer powerful insights into holistic problems, within healthcare and can strengthen and enhance students’ awareness. The use of this teaching approach exposed students to holistic care principles across care settings.

In line with the general findings in the literature, the use of cancer patients’ narrative and real stories offered to students some ways of cognitively realigning patient’s experience, thus enabling more effective comprehension of their needs [10,13]. The exploratory purpose of the investigation, carried out through the evaluation sheets, was to identify the component of the methodology adopted in this teaching session, as aspects related to learning, applied implications in clinical practice, and acquired skills. Students expressed that the narrative of illness and hospitalization increased their awareness of the patient-centered-care [6,7].

This teaching strategy helped them learning about patient’s experience, considering that the narrative helped them to assimilate theory and practice and encouraged them to seek more learning elements [12]. We think that using this teaching-learning method, students were not oriented to consider only the disease, but also to understand the impact that the disease can have on the person and his/her family, as well as on the workplace and on the social environment [18,19], in physiological, psychological and spiritual ways to finally implement some care interventions that can meet the real needs and hopes of cancer patients.

Conclusion

We feel that patients’ narrative and story told in their own words can provide a useful contribution to nursing undergraduate education, in order to provide comprehensive, holistic, and individualized care. Students found this to be an interesting learning approach, which aided reflection on the personal meanings of serious illness.

The implementation of educational actions such as those described above, encourages students to be more competent and responsive in supporting patients in this particularly situation and to develop the capacity to understand the wholeness of the patient (body, mind and spirit).

The gain of basic interpersonal relationship and communication skills towards the cancer patient and his family, represents an essential component to improve the quality of nursing care processes and to increase the medical staff’s human side hence to be able to turn despair into hope. A powerful tool that helps students to understand connections between patient’s experience and professional practice has been highlighted from patients’ voice in a significant way.

Literature about real patient’s story effectiveness should, and could, be used in clinical practice. New qualitative studies about the use of narrative at several stages of nursing education may shed further light on the benefits of narrative to better understand the real experiences of students in this teaching process and in clinical practice.

References

- Arrigoni C, Grugnetti AM, Caruso R, et al. Nursing students’ clinical competencies: A survey on clinical education objectives. Ann. Ig 29(3), 179-188 (2017).

- Bagnasco A, Galaverna L, Aleo G. et al. Mathematical calculation skills required for drug administration in undergraduate nursing students to ensure patient safety: A descriptive study. Drug calculation skills in nursing students. Nurse. Educ. Pract 16(1), 33-39. (2016).

- Grugnetti AM, Arrigoni C, Bagnasco A, et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of calculator use in drug dosage calculation among italian nursing students: A comparative study. IJOCS 11(2), 57-64 (2017).

- Denzin NK. The research act: a theoretical introduction to sociological methods. Englewood Cliffs, N.J. Prentice-Hall (1989).

- Durgahee T. Reflective practice: nursing ethics through story telling. Nurs. Ethics 4(2): 135-246 (1997).

- Costello J, Horne M. Patients as teachers? An evaluative study of patients' involvement in classroom teaching. Nurse. Educ. Pract 1(2), 94-102 (2001).

- Bleakley A. Stories as data, data as stories: making sense of narrative inquiry in clinical education. Med. Educ 39(5), 534-540 (2005).

- Demir F, Donmez YC, Ozsaker E, et al. Patients’ lived experiences of excisional breast biopsy: a phenomenological study. J. Clin. Nurs 17(6), 744-751 (2008).

- Coyle N. In their own words: seven advanced cancer patients describe their experience with pain and the use of opioid drugs. J. Pain. Symptom. Manage 27(4), 300-309 (2004).

- Fain JA. Nursing: read it, understand it, and apply it (2nd ed) Milano: McGraw-Hill (2004).

- Haigh C, Hardy P. Tell me a story-a conceptual exploration of storytelling in healthcare education. Nurse. Educ. Today 31(4), 408-411 (2011).

- Favoreto CAO, Camargo Jr KRC. Narrative as a tool for the development of clinical practice. Interface Comunicacao Saúde Educacao 15(37), 473-483 (2011).

- Cheng KKF. Oral mucositis: a phenomenological study of pediatric patients’ and their parents’ perspectives and experiences. Support. Care. Cancer 17(7), 829-837 (2009).

- Abdel Razek A, Az El-Dein N. Effect of breast-feeding on pain relief during infant immunization injections. Int. J. Nurs. Pract 15(2), 99-104 (2009).

- Edwards SL. The personal narrative of a nurse: a journey through practice. J.Holist. Nurs 20(10), 1-8 (2015).

- Distler J. Critical thinking and clinical competence: results of the implementation of student-centred teaching strategies in an advanced practice nurse curriculum. Nurse. Educ. Pract 7(1), 53-59 (2007).

- Ferreira VT, Guirro EC, Dibai-Filho AV, et al. Characterization of chronic pain in breast cancer survivors using the McGill Pain Questionnaire. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther 19(4), 651-655 (2015).

- Arrigoni C, Caruso R, Campanella F, et al. Investigating burnout situations, nurses’ stress perception and effect of a post-graduate education program in health care organizations of northern Italy: a multicentre study. G Ital Med Lav 37(1), 39-45 (2015).

- Caruso R, Miazza D, Berzolari FG, et al. Gender differences among cancer nurses’ stress perception and coping : an Italian single centre observational study. G. Ital. Med. Lav 39(2), 93-99 (2017).